Testing is key to safe drinking waterWhether it's from a tap or a bottle, many samples yield bacteria and arsenicBy MOLLY MURRAY / The News Journal

|

||||||||||||||||||

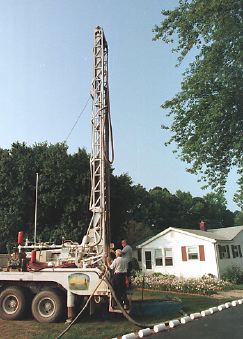

The News Journal/GARY EMEIGH |

|

| The majority of Kent and Sussex residents get their drinking water from private wells, including this 60-foot one near Willow Grove. | |

| S P E C I A L R E P O R T | |

| A R T I C L E S | |

| DAY 1 • State's waters are rank with sewage • Water filled with signs of decline • Clams cause worry in Inland Bays • Blue crabs feeding grounds barren • How you can help DAY 2 DAY 3 |

|

| G R A P H I C S | |

|

Combined Sewer Overflows |

|

Delaware rivers graded for aquatic life |

|

Delaware rivers graded for human contact |

Hundreds of Delawareans buy and drink bottled water, often because they don't trust the quality of water from the tap.

But bottled water may not always be better.

As an experiment - just out of curiosity - Rick Duncan, chief staff officer with the Delaware Rural Water Association, a nonprofit group that works to ensure the quality of drinking water, decided he would run a test on a brand of bottled water.

"I'm not going to say which one," Duncan said. "We did a bottle of water and actually found trace amounts of arsenic in it."

The nonprofit environmental group the Natural Resources Defense Council found that about one-third of the bottles it tested contained some contamination ranging from inorganic chemicals to bacteria to arsenic in a 1999 study.

Still, the International Bottled Water Association, an industry trade group, points out that bottled water is regulated as a packaged food under U.S. Food and Drug Administration rules.

In Delaware, the water you drink from the tap may get more scrutiny than bottled water, or no scrutiny at all - depending on where you live.

Duncan and his staff are using specialized kits to get a baseline snapshot of what's in tap water in Delaware.

A set of chemicals is used to develop a scale that can be used to measure change when a new test is done.

If there is a 20 percent deviation in subsequent tests, it is a sign "something has drastically changed," Duncan said. The project is funded with a grant from the state Division of Public Health.

Because of their fears about the quality of tap water in Delaware, many residents buy bottled water.

"For me, it's a little frustrating because I know the lengths we go to," to make sure tap water is safe to drink, said Anita Beckel, the state's public water-supply program manager.

Once a year, municipalities and communities publish a report on drinking-water quality.

And most of the time, the news is good.

All public water supplies from Wilmington south to Selbyville are tested for contaminants, which is a mandate from the federal Environmental Protection Agency. Public water supplies include municipalities, developments served by central water systems, places with 15 or more water-supply connections, and establishments that regularly serve more than 25 people, such as child care centers and factories.

The supplies are tested for contaminants that range from microorganisms, such as coliforms, to disinfection products to arsenic, copper, fluoride and some agricultural herbicides.

Coliforms are bacteria. Though they generally do not cause disease, coliforms indicate the presence of organisms that may be pathogenic. Fecal coliforms indicate the possible presence of fecal contamination from warm-blooded animals.

Municipalities and other public water supplies do sampling based on a set of criteria. In Wilmington, for instance, there are dozens of tests for bacterial contamination each month, Beckel said.

People who get their water from individual wells on their property or from a community well may not know the quality of the water they drink unless they have it tested. Test kits that check for the nitrogen contamination cost $4 and are available from the state health department. Homeowners collect their own sample using the test kit, send it in and about two weeks later get results back.

The most common contaminants in Delaware are nitrates and bacteria.

Nitrogen gets into drinking water through runoff from fertilizer, leaching from septic tanks and sewage. Levels above 10 milligrams per liter are a concern, and experts urge people who have contaminated well water to drink bottled water.

Infants exposed to water tainted with excessive nitrogen can become seriously ill and may die, if untreated. Nitrogen can lower oxygen levels in a baby's blood. Nitrates are a problem for people who have shallow wells, particularly downstate, where there are a lot of poultry farms.

Contaminants are usually measured in milligrams per liter. A milligram per liter equals one part per million. About three-hundredths of a teaspoon dissolved in a bathtub full of water equals one part per million.

Bacteria, which can cause gastroenteritis and flulike symptoms, can come from septic systems, cesspools and sewage, or runoff from animal farms. Bacteria also can taint water supplies when ground-disturbing construction work is done near underground water pipes.

Beckel said state officials also look for MTBE, a gasoline additive that has contaminated groundwater in some parts of the country, including a few wells in Delaware. They also look for agricultural chemicals. Lindane, a pesticide, has been found in some water samples in Delaware, she said. In addition, a chemical used in dry cleaning has caused problems in some areas of the state, she said.

HOW YOU CAN HELP

- Pump your septic tank every one to five years, depending on the volume of water use and the number of people in the home.

- Watch what you flush down toilets. Sewage-treatment plants are designed to treat human waste. Chemicals, plastics and solids can disrupt treatment.

- Check recent recommendations for lawn fertilizers and have your soil tested. Excess fertilizer can run off into the Inland Bays.

- Don't overuse chemicals on your lawn. Follow directions carefully for lawn-treatment programs.

- Consider natural methods of pest control. For example, get neighborhood kids to collect Japanese beetles, and pay them for each jar they collect. Don't kill snakes, and remember, wasps and dragonflies are predators of other insects. Don't automatically kill them.

- Learn about Delaware's water-quality standards and keep up with proposals to change them.

- Test private drinking-water wells annually for nitrate contamination. Home test kits are available from Division of Public Health offices in each county. Contact (302) 739-5410 for information and office locations.

- Read a Delaware fishing map and find out which fish are safe to eat.

- Learn which areas are safe for swimming and wading, and keep up with state swimming advisories at http://www.dnrec.state.de.us/DNREC2000/Beaches.htm.

- Find out how your city or county wastewater-treatment plant rates by checking http://www.epa.gov/enviro/.

- Find out what's in your drinking water by studying the Consumer Confidence Report issued by your town or water company.

- If you have a small yard, use a reel lawn mower to conserve energy, and reduce yard waste and air pollution that can contaminate rain and harm waterways.